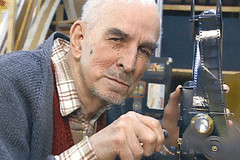

R.I.P. - Ingmar Bergman

Film great Ingmar Bergman dies at 89

By Duane Byrge

July 31, 2007

Ingmar Bergman, one of the leading influences in the development of cinema whose films probed the mysteries of human existence with indelible imagery, died in his sleep Monday at his home on an island off the coast of Sweden. He was 89.

With more than 50 feature films to his credit, together with more than 100 theatrical productions, the Swedish director gained an international following with works often inspired by Scandinavian theater and its richly developed themes of religious ritual, romantic passion and family tradition.

Three of Bergman's works won Oscars for best foreign-language film, and he was personally nominated nine times. In 1971, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded him its Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award.

Religion and reflections on ethical and philosophical issues were his subject matter. His films, which reverberate with philosophical and psychological themes, became the most revered of the century, including "The Seventh Seal," "Persona," "Shame," "The Passion of Anna," "Cries and Whispers" and "Fanny and Alexander."

While his films evolved in distinct stages over more than five decades, his visual style -- intense, intimate, complex -- explored the depths of the human psyche as well as man's place in the universe with an intensity and cadence that has been itself an artistic correlative for Bergman's narrative themes.

His name has become synonymous with "serious" filmmaking, and his works have inspired many filmmakers, among them Woody Allen, whose reverence for Bergman can be found in many of his own works, both comic and serious. Allen once described Bergman as "probably the greatest film artist ... since the invention of the motion picture camera."

"Bergman was the epitome of a director's director -- creating beautiful, complex and smart films that imprinted permanently into the psyche -- inspiring filmmakers all over the world to create their own movies with similar passion and brio," DGA president Michael Apted said.

The DGA recognized Bergman with its highest honor, the Lifetime Achievement Award, in 1990. The Festival de Cannes, celebrating its 50th anniversary in 1997, also honored him with its Lifetime Achievement Award, an honor the reclusive Swede declined to accept in person. He remained during the course of the May festival at his isolated home on the Baltic island of Faro off the coast of Sweden.

Responding to the news of Bergman's death, Cannes Film Festival director Gilles Jacob called the director the "last of the greats, because he proved that cinema can be as profound as literature."

The son of a Lutheran clergyman and a housewife, Ernst Ingmar Bergman was born in Uppsala, Sweden on July 14, 1918, and grew up with a brother and sister in a household of severe discipline that he described in painful detail in the autobiography "The Magic Lantern."

The title comes from his childhood, when his brother got a "magic lantern" -- a precursor of the slide-projector -- for Christmas. Ingmar was consumed with jealousy, and he managed to acquire the object of his desire by trading it for a hundred tin soldiers.

He broke with his parents at 19 and remained aloof from them, but later in life sought to understand them. The story of their lives was told in the television film "Sunday's Child," directed by his own son Daniel.

To break into the world of drama after dropping out of college, Bergman started with a menial job at Sweden's Royal Opera House.

In 1942, he found work revising scripts for Sweden's largest production company, Svensk Filmindustri. In 1944, he wrote an original screenplay titled "Frenzy," and Alf Sjoberg, the country's most respected filmmaker, was selected to direct. That same year, Bergman was appointed director of the Municipal Theatre in Helsingborg and later worked in theater in Goteborg and Malmo. He garnered excellent theatrical reviews, which paved the way for directing films. Bergman directed his first feature film, "Crisis," in 1945.

The young Bergman went on to make a succession of films, bursting onto the international scene with "Smiles of a Summer Night," an inventive comedy of manners that was a hit at Cannes in 1955. The film was adapted to the musical stage by Stephen Sondheim in 1973 as "A Little Night Music" and also inspired Allen's 1982 comedy "A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy."

The Cannes accolades prompted Svensk Filmindustri's financing of Bergman's pet project, "The Seventh Seal." An intriguing mystery set in the Middle Ages when weary Crusaders were returning to Sweden only to confront the Black Death that was sweeping across Europe, the film quickly became a classic. It is still screened with regularity in college film societies and at film schools throughout the world. The haunting film starred Max Von Sydow as a knight who encounters Death, a role that launched his international film career.

Bergman's eye for acting talent was sharp, and many young Scandinavian players went on to international stardom as a result of playing in Bergman's films; in addition to Von Sydow, they include Liv Ullmann, Ingrid Thulin, Bibi Andersson and Harriet Andersson.

Bergman's success and development as a filmmaker continued apace in the '50s. His "Wild Strawberries" won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1958. A piercing exploration of childhood through the memories of old age, the film was remarkable for Bergman's creative use of the close-up, etching vividly the inner psyche through the contours and expressions of the human face.

"The great gift of cinema photography is the human face," Bergman once said, indicating that it was his dream someday to make a film that would be a two-hour close-up of a human visage.

The late '50s saw Bergman further widening his craft as he merged his cinematic aesthetic with his philosophical, psychological and religious themes. His subjects were "big": "The Magician" explored the supernatural; "The Virgin Spring" tapped into a dark eroticism; and "Through a Glass Darkly" explored the Western notion of God, probing what Bergman regarded as an inherent destructiveness in Christianity.

"Mr. Bergman's power to convey complicated philosophical reflections upon the nature of man and society, all through the cinematic medium, is so great that it makes one gasp," the New York Times wrote in its "Magician" review.

"Virgin Spring" won the Oscar for best foreign-language film in 1961, and the following year, "Through a Glass Darkly" captured the same high honor. Film scholars regard that film as the beginning of a dark trilogy for Bergman that included "Winter Light," a penetrating look at human loneliness, and "The Silence," a sexually charged portrait of spiritual malaise and a work that prompted vigorous opposition from censors in Sweden and France. All three films were photographed by the late Sven Nykvist, whose stark and dark framings were in sync with Bergman's dark-eyed narratives and themes.

Light and shadow were crucial to Bergman's philosophical narrative palette: In 1968, he began a series of austere works that were designed to evoke the essence of "darkness." "Hour of the Wolf," "Shame" and "The Passion of Anna," his films made during the cataclysmic period of the 1960s, were fraught with issues of social and political responsibility. They brought him both praise and condemnation.

His next film, "Cries and Whispers" -- a sensual and anguished observation of solitude -- was widely lauded by his ever-growing legions of cinematic disciples. He followed that up with a six-episode TV project, "Scenes From a Marriage." It starred Ullmann and Erland Josephson, and the series was dubbed for rebroadcast in the U.S. and the U.K. It was later condensed for theatrical release as well.

Bergman's scope widened in the '70s. He filmed Mozart's opera "The Magic Flute" as well as "Autumn Sonata," which starred Ingrid Bergman. That cycle of Bergman's work aptly concludes with "Fanny and Alexander," a family story that is part fairy tale and part ghost story. Although he continued to write screenplays -- "The Best Intentions," "Sunday's Children" -- he essentially stopped making feature films after "Fanny," focusing instead on a number of television projects.

After the release of "Fanny," Stockholm's leading newspaper, Svenska Dagbladet, wrote that Bergman is "a director who has looked deeper than most people into the shadows of existence and the human psyche, but who, after the nightmares of many films, now seems to have reached a clarified and harmonious reconciliation with life."

"Saraband," a TV film he completed in 2003, proved to be Bergman's last directorial effort. Once again, he turned to Ullmann, who appeared in 10 of his films, to star in the family drama.

Bergman was married five times and fathered nine children, including a daughter Linn Ullmann, whose mother was Liv Ullmann, his partner in a five-year affair.

The date of Bergman's funeral has not been set, but will be attended by a close group of friends and family, the TT news agency reported.

Gregg Kilday and the Associated Press contributed to this report.

<< Home